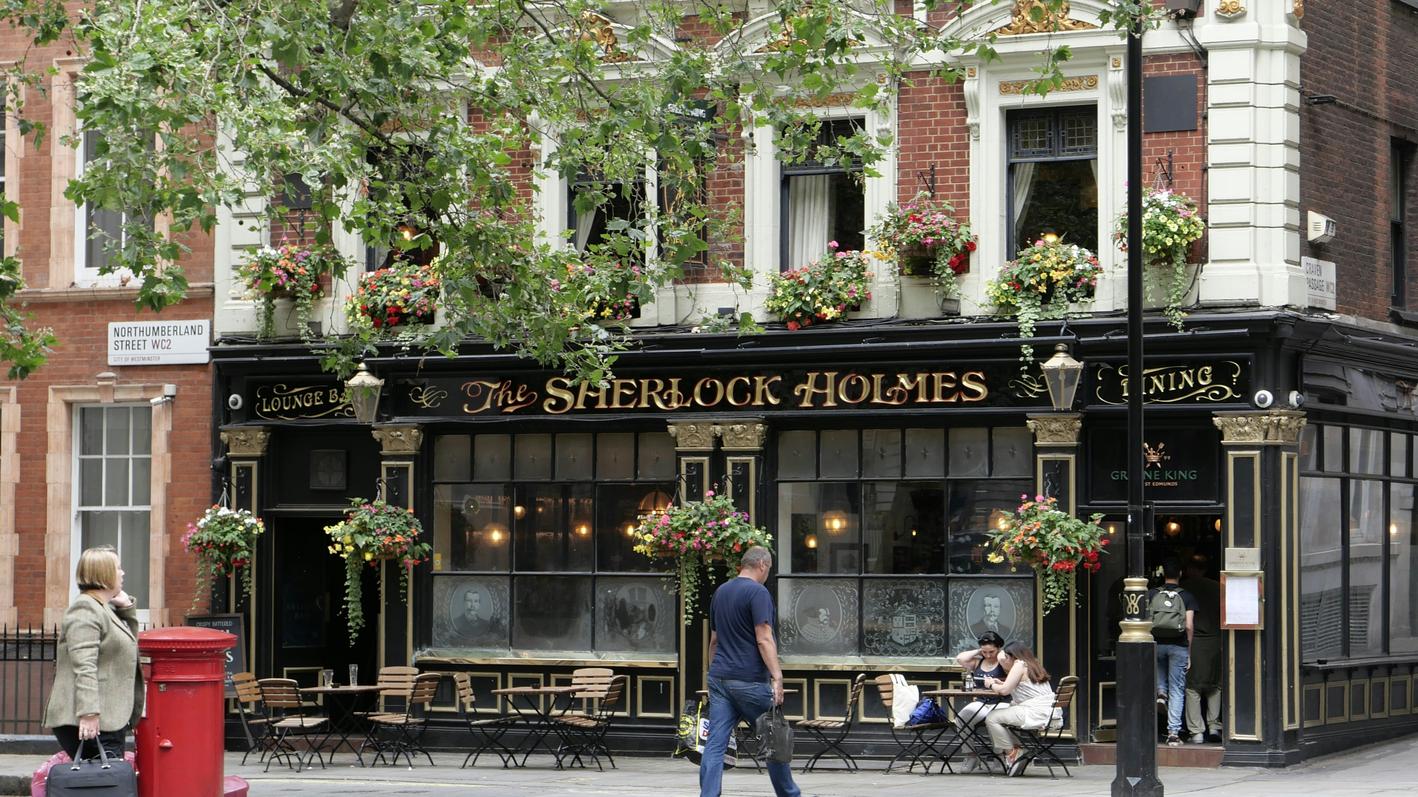

Matthew Bellringer helps neurodivergent people work in ways that support them and their unique strengths. For Matthew, Sherlock is a great model for understanding both the gifts of a neurodivergent brain, and the challenges that come with it.

Holmes is almost unfunctional without Watson. He can’t talk to people properly without offending them. He can’t do half of the stuff he needs to do, he can’t turn up in the right place very often. He needs Watson, and they understand that in their relationship.

What I really like about the way that Holmes approaches the world is he understands where he’s strong and where he’s weak, and he brings in other people to do that. And what I really enjoy is how clear that boundary is and how it’s absolutely a no.

One of the first things Watson discovers about Holmes is the bizarre gaps in his knowledge, my favourite being that the great detective is completely unaware that the earth moves around the sun and not the other way around, and better still, that knowledge holds absolutely no interest to him because it’s not relevant to his work.

Now, two things are important to say at this juncture. Firstly, Sherlock Holmes is not, no matter how many monuments, societies, and walking tours that happen in his name, is not and never was a real person.

So let’s not dwell too much on whether or not a character who only existed in words that were typeset well over a century ago might or might not have certain neurodivergent traits. But if we assume that he did, what do we really mean by neurodivergence? And what’s the difference between neurodivergence and neurodiversity?

Everyone is neurodiverse in the sense that we all differ in terms of our lived experience as a result of differences in neurology. So all of us think and feel and experience the world somewhat differently. However, within that overall variation, some people like quite significantly outside of the cultural social expectations about how brains are supposed to work or how brains do work. And we tend to call those groups neurodivergent sometimes neuro-atypical as well I’ve seen as well.

And that might be associated with a specific diagnosis like A DHD or autism dyspraxia. Dyslexia to Tourettes. but it also might not, I mean, it can also just mean fundamentally working from a very different experience. That’s the really important idea. The distinction is so everyone is neurodiverse at a population level, but no individual can be neurodiverse. That doesn’t make sense really. Um, but some people are neurodivergent and have that really quite considerable difference in experience and thinking, and feeling on an ongoing basis compared to the way that most people mostly think and feel.

So the next time your uncle tells you, over the dinner table, that “we’re all a little bit autistic, aren’t we?” you can kindly remind him that no, we’re not, but we exist on a spectrum, and some people experience the world in some specific ways more than others.

So we’re not in the business of diagnosing other people – and we’ll get onto that in a bit – but we can say that Holmes, as written by Conan Doyle, exhibits traits of both autism and ADHD.

Sherlock Holmes and ADHD

And I wanna stick with the word “traits” here because, whether or not you’re looking for a formal diagnosis of your own, understanding how you behave and what you need can be really helpful.

Your experience of the word is valid, whether or not you have a diagnosis to back that up, that’s the important thing. Whether or not you feel comfortable using the label and other people feel comfortable with you using the label is a slightly different matter. But the most important thing is to know that whatever anyone else says, your experience way you experience the world is true.

If you find yourself flitting between interests – trying something for a few days or weeks, putting down and then looking for the next thing – you might have an experience that tallies with someone that has ADHD.

One of Holmes’ special interests for a time was cigarette ash. He wrote the equivalent of a long-read blog post listing different types of tobacco ash and how to identify them, a piece of writing he’ll mention about as often as a vegan tells you they’re vegan.

This sort of magpie mind is often drawn to the world of productivity, as there’s always a new system to try… and we can tell ourselves that we’re improving our efficiency or getting more organised… and that may be true, but we’re also fuelling our insatiable need for novelty. Back to Matthew.

Having a magpie mind, a high novelty seeking need, is a very common experience of ADHD. It’s not a universal experience of ADHD and it’s not just people with ADHD who have high novelty seeking, and that kind of magpie mind, shiny thing.

So it’s useful to be able to understand, and I think talking about these as experiences, it’s like understanding, “I experience the world this way” is actually a more helpful way, very often of, of working with this stuff, than saying “I have ADHD and therefore…”

The thing we need to watch out for, if we have that kind of novelty-seeking mind, is that we don’t let playing with a new system get in the way of doing the actual work. It’s a refrain that goes back to our discussion on the Bullet Journal method, and if you’ll permit me, I’d like to express it like this.

The rhythm of productivity

The system you use for organising your work and your time should be like the rhythm section in a tight band. It literally keeps time, and it underpins everything else the band does. Without it, the piece turns to chaos.

Rhythm is essential in most music – especially the kind people actually enjoy, rather than the stuff polo necks pretend to like in order to impress other polo necks – but it isn’t the star. Occasionally, especially if you see a band live, you want to hear the drummer properly let it rip all over the kit. But not every piece should sound like the movie Whiplash.

Your work – the stuff you’re actually on this earth to do – is the melody, and your life is the chords underneath. If you keep changing the tempo or the time signature, you disrupt the other musicians in the band. So sometimes, what we have to do is find a system that works well enough for now, even if it’s not absolutely perfect, because chances are it won’t be… and throwing all your stuff into the newest app or the next trending method is going to leave you knackered.

Also, not all systems are created equal.

If I’ve got the greatest notation system in the world, if I have to copy and paste a tonne of stuff every day into that, I’m never gonna use that after the honeymoon period, because that’s gonna become tiresome very quickly; It’s very low value work.

So how does it integrate? How little maintenance does it need? Because when we start out, when things are fun and novel, the maintenance is fun. But as soon as it gets boring, the maintenance is a chore.

As someone who keeps trying to move his entire life into Notion, I can wholeheartedly agree. I love the idea of “the everything app” that can act as my second brain and store all the stuff I need to know and think about, but you’ll pry my todo app from my cold dead hands.

One of the reasons you might find yourself jumping between different systems is that no one system quite covers all your needs or reflects the way your brain works. So for that, we want to create our own individual productivity method, and that’s where we start getting all scientific.

Deductive reasoning

When Sherlock Holmes approached a new case, he went in curious. He studied the scene of the crime in as much detail as he could. He asked questions of everyone who was there, and used his method of deductive reasoning to get to a conclusion.

When we read a book like Getting Things Done or Building a Second Brain we can be tempted to think “Right, this is the way forwards. Let’s get everything into this new system”. And then something crops up that doesn’t fit that system and gradually things start to fall apart. These self-help books are great at showing us just how marvellous and miraculous it can be to organise our lives into these neat boxes, but if you’ve ever tried to take a cat to the vet, you’ll know just how dangerous it is to try and force a physics-defying object into a finite space.

So the key is to start with tiny experiments. Begin with a hypothesis – a “reckon”, if you will – and test it out over a period of time.

Aa lot of services have free trials because they understand you put a tonne of effort in, you set it all up how you like it, you’re committed, then you’re gonna pay the subscription fee. So being really, really careful with your experiments, also being clear upfront as possible about what it is you’re trying to find out.

That’s the key. if you’re going to try out a new system, what are you hoping to get out of it? Is it meant to save you time? Is it meant to help you stop forgetting stuff? Is it to help you stick to commitments you’ve made? If you find, after a bit of time that the system you’re trying isn’t meeting those needs – or it has its own set of needs which get in the way – then you can either discard it entirely, or see if there’s a little bit you can cherry-pick from it and move on.

Armchair diagnosis

Earlier we talked about diagnosis, and whether it’s something you want to seek out. And while I’m really glad a lot of people are sharing their experiences online and encouraging others to learn more about themselves, there’s a teeny tiny red flag we need to watch out for.

It’s about people

As Matthew suggested right at the top of the episode, Holmes was not necessarily the most functional of people, and the intricate workings of those meat sacks didn’t come easy to him.

I’ve talked before about the importance of other people in our productivity methods, because while it’s all well and good protecting your time, we don’t exist in a vacuum.

For example, I work to time bounding, but I have a system that is flexible up until all the time is used, and it arranges things so that I’ve got specific things that I need to do.

I don’t have a very strong sense of “maybe I want to do that one in the afternoon and that one in the morning”, but each one of those takes an hour. So it kind of doesn’t matter when people book in as long as I get those done within bounds.

So having a system with a bit of flex in it is really, really helpful because that then allows other people to flex a bit.

And this is one of the risks of really complicated systems, is there can be quite brittle if they encounter something unexpected for you as well. And I’ve seen people fall out of entire systems because if it feels like it’s all gonna break if you miss one day and you’re gonna be recoverable, that’s gonna happen at some point.

At some point the day’s gonna get beyond your control, that’s just life. So if the system can’t deal with your own needs and for flexibility as well, and it all falls to pieces, then that system is overcomplicated and too brittle.

Holmes had his mind palace, Watson his notebook. Each of us has a way of keeping track and keeping time, and the key is to find the best possible option – or the least bad combination of options – that works for us, and to remember that life is going to rattle the bars of your system.

When Holmes wasn’t occupied with a case, he took recreational drugs because he just needed that altered state. His mind was a terrifying hall of mirrors as much as it was a palace, but thankfully he had Watson as his support structure.

Whatever you’re undertaking in life, whatever your big work is – or the work you’d rather be doing than paying the bills – make sure you’ve got something to lean on. Systems are flexible up to a point, but people will always provide far more support.