It’s been many years since I’ve played The Sims, but one of my friends has built an elaborate world full of drama and intrigue. I mean for me, most of my amusement came from locking my Sims in a bathroom and building a wall between them and the toilet, so they got bladder failure and wet themselves.

Each Sim is a complex assortment of pixels and code. They have meters for various needs and skills, and their behaviour affects other characters in the game.

We – and I’ve checked this – are more complex than characters in The Sims, yet we often give ourselves a hard time when we’re not achieving our best or working at our most efficient pace. But just like one of those little adorable isometric meeples, we can dial up the things that make us more productive, and watch what happens when our resources are depleted. And we can notice how we’re affected by the world around us, and how we, in turn, affect others.

Taylorism revisited

Idea comes in, something happens, then creativity comes out. Similarly, the harder and more efficiently you work, the faster you can churn out high-quality product. Right?

Meh, maybe in the 50s when it was thought that raw beef plus unskilled labour could deliver a delicious cheeseburger in a minute. But the world – and the people who inhabit it – are far more complex, and the work we do is, for most of us, far more complex than slapping a patty in a bun and being professionally indifferent to your customers.

Modern work needs a more modern approach. Enter systems theory, and one of its greatest proponents.

Hello Bucky

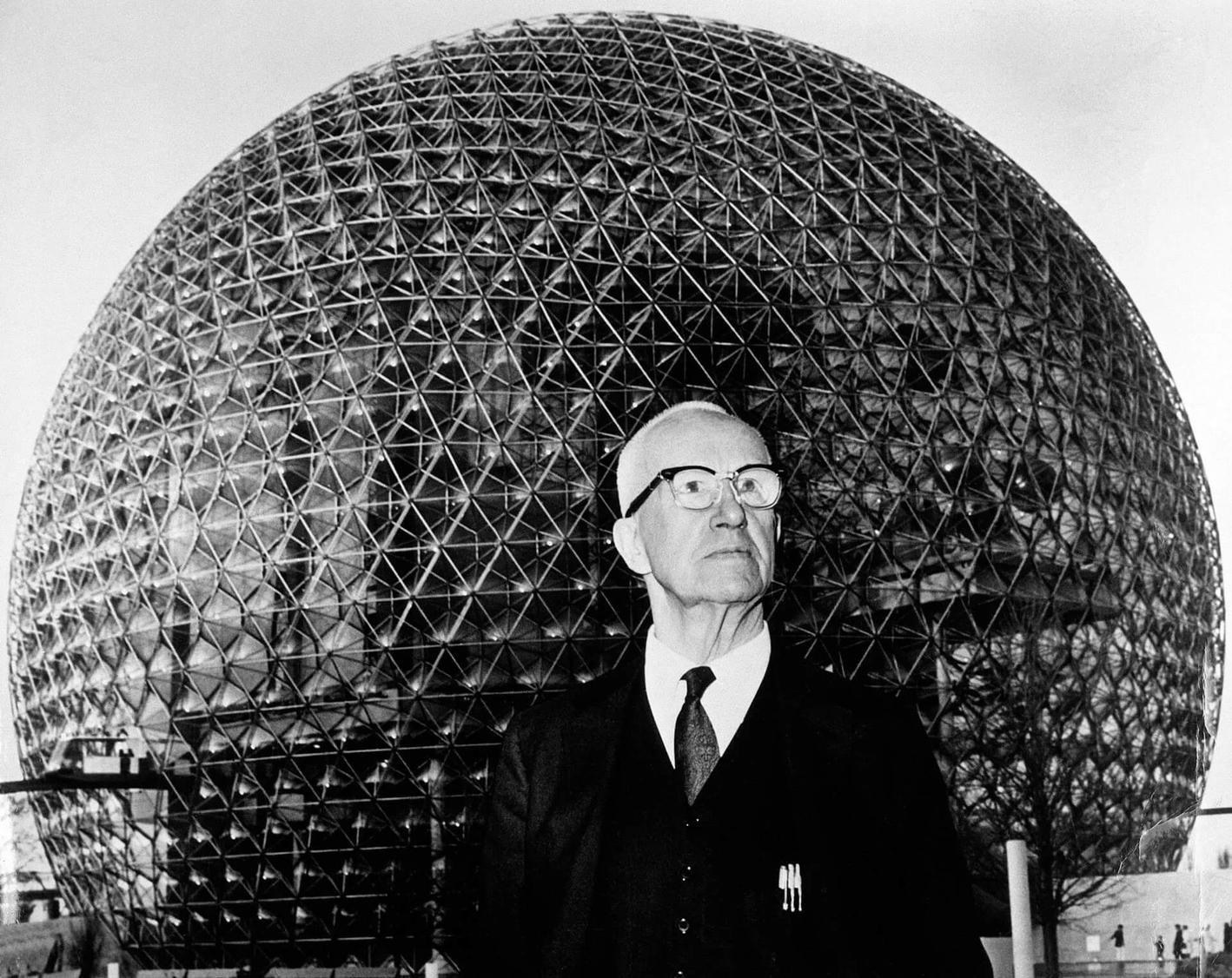

Richard Buckminster Fuller was born in Massachusettes in 1895, just three years before the world first met last week’s focus, Sherlock Holmes.

He was designing and inventing by the age of 12, and was expelled from Harvard for going broke partying with a vaudeville troupe, and again for his “irresponsibility and lack of interest”. What an absolute lad.

After uni, he joined the navy and worked in the meat packing industry. He married in 1917 and a year later had a daughter, who died of complications from polio and spinal meningitis just before her fourth birthday.

He suspected his damp and drafty house was a contributing factor to his daughter’s death, so started work on designing a new kind of affordable housing, which would eventually give rise to the geodesic dome he’s so famous for… if you’ve seen the big golf-ball looking thing in Disney’s EPCOT centre, you’ll know what I mean. Incidentally, the attraction housed in the golf ball is called Spaceship Earth, which is a term also coined by Buckminster Fuller.

Bucky, as he’d come to be affectionately known, had a pretty rough go of it, going broke, experiencing depression, heavy drinking, and on one particularly dark day, contemplating drowning himself in a lake so his wife and newly-born daughter could benefit from the life insurance.

But he was stopped at the lakeside by a voice, and a sensation of being lifted into the air and suspended in a white sphere of light. The voice said to him

From now on you need never await temporal attestation to your thought. You think the truth. You do not have the right to eliminate yourself. You do not belong to you. You belong to the Universe. Your significance will remain forever obscure to you, but you may assume that you are fulfilling your role if you apply yourself to converting your experiences to the highest advantage of others.

The day episode one of this show came out, I was up a mountain taking magic mushrooms. I didn’t receive quite that eloquent a talking-to, but I did discover that I was tremendous company, and that the world was kind of like a big screw, and you just had to keep following the thread down.

Anyway, I dunno if Bucky was on shrooms when he heard this voice, but it kicked off a journey of discovery into the many and varied ways he might benefit mankind. Again, what an absolute lad.

The late 40s and 50s saw him work on the geodesic dome designs he’s probably most famous for. He didn’t invent the structure but popularised it, and was contracted by the US military to build small geodesic buildings, which are more energy efficient than square ones.

Fuller was an environmentalist, and saw the earth as a system. He coined the term “Spaceship Earth” to describe such a system, and how mankind needed to club together to conserve the planet’s finite resources. He also coined the term “Synergetics”, a method for trying to understand the ways nature organises itself.

And it’s this theory of systems that we’re going to get into, so please pull down on the lap bar, secure your belongings, and keep your hands and arms inside the car at all times.

Systems theory

If you look to your left, you’ll see a working scale model of a mysterious machine. We don’t know what the machine does, but it has three important components: an input, a process, and an output.

Now we can see the inputs going into the machine. There’s the energy needed to keep the machine running, the people shovelling the raw materials into the furnace, and the materials themselves. These are all necessary parts of the input, and they’re all complex machines of their own, that work independently but come together to make this bigger machine work.

Now we move on to the process. That’s the shovelling of the materials, the grinding of the gears, the humming of the valves, and the mangles that wring out all the reclaimable matter from the raw materials.

And finally at the back end of the machine, we have the output; tiny cubes pooped out of the machine, shrinkwrapped and ready for consumption. If you’d like to pick up a sample of the end product, you’ll find it in the gift shop.

How does this apply to us?

We are, like that machine, a system, and our work comprises inputs, processes, and outputs. If you start to divide yourself and your work up in this way, it becomes a bit easier to understand how we keep the whole thing running. So let’s start with inputs.

If you do creative work, you can’t do that if you’re completely knackered and lacking any kind of inspiration – you can’t, as they say, pour from an empty cup.

When you start to see yourself as a system, you can recognise that this isn’t just Instagram self-care bollocks, but something necessary for the machine that is you, to function.

Energy and ideas are really the two biggest inputs you need, but time is also a factor, and all of these inputs come from other systems which are themselves a collection of inputs, processes, and outputs. That’s why I’ve been wanging on about how people matter in your productivity story too, because how you work with them affects how your own system functions.

Artists’ dates

One of the ways Julia Cameron, author of the book The Artist’s Way recommends you keep your inspiration topped up is by going on what she calls “artists’ dates”. These are things you ideally do on your own, and that are solely there to help you fill up on inspo.

It could be going to see a film or some standup, grabbing a dirty burger at the food truck you’ve been meaning to check out, or wandering around your local arts centre or gallery. The film doesn’t have to be good, the standup doesn’t have to be award-winning, and the art doesn’t need to make you scratch your chin and look all wistful. What matters is you’re taking stuff in for your machine to chuck around like forgotten socks in a dryer.

But, as I’ve said before, dedicated time to work on your craft is also an important input. If you’re looking to create something outside of your day job, you need to carve out some time where you can do that. If you’ve got a partner and you can work on your project while you’re both in front of the TV, that’s much better than cloistering yourself off in another room… again, the other people in your life are systems, and you might be part of their input, too.

if you don’t have enough of the right inputs, you can’t move onto the next stage, which is the process – the actual doing of the doing. Here you’ll turn your raw materials – your time, your energy, your inspiration – into something.

Remember though, that these materials are finite. If I want a coffee from my little Dulce Gusto pod machine, it’s not enough to put the pod in and turn on the machine; I also have to make sure the water tank is topped up, otherwise the thing is going to cough and splutter and I’ll probably end up with a cup of frothy smoke.

This, hopefully though, is the fun bit. This is where you’re actually doing your art, where you’re in flow, and where the work doesn’t necessarily feel like work. That’s not always the case of course, so if you’re not feeling it on one particular day, you might end up using more energy than usual.

So if you find your process isn’t running smoothly, try and think of your inputs as little glass tubes full of different-coloured liquids: a red one for time, a green one for energy, and a blue one for inspiration. Delete as appropriate if you’re colour-blind. If the process is stalling or something’s gumming up the works, check your tubes to see if something’s running low. That process will make it easier for you to diagnose what’s wrong.

Equifinality

This theory came up as a response to the prevailing management style of the time, which was essentially Taylorism. We covered Taylorism a bit in our discussion on two of the forgotten women of productivity history, so I won’t go into it in detail. Suffice it to say that equifinality is the idea that there is actually no “one right way” to do something, which is in direct contradiction to Taylor’s idea that every task has, at its core, one correct method.

Let’s say you live in the city and you want to take a trip to the beach. However far away you are, you need to plan how you’re going to get there. Under Taylorism, there should be only one correct route, because everything’s been broken down into its simplest parts. Systems theory, on the other hand, recognises that the conditions for the ideal route might not be conducive, so you need to pick an alternative option.

That adaptability is pretty useful for us when it comes to our own productivity. If you don’t get to choose your optimal working environment, are there some reasonable adjustments you can make? If you’re in an open plan office and you need to concentrate on summarising a report but the hobbit from IT is flirting with Janet from Accounts Receivable – that’ll never work, by the way, they’re just not compatible – then maybe you can pop on some noise cancelling headphones for a bit.

If your boss insists everyone’s ear flaps remain open, no amount of scrunching up your face and huffing and puffing is going to make your job any easier, however simple the process of putting one word in front of the other might seem.

And what might sound like a chaotic office environment is actually the result of lots and lots of interconnected systems, each with their own inputs, processes, and outputs. Chaos theory is inextricably linked to systems thinking, so because I can’t afford that clip of Jeff Goldblum from Jurassic Park, I’m going to demonstrate the idea of the seemingly unconnected being very much connected, by explaining why it’s harder to buy Gummy Bears when people stop buying cars.

Chaos, the Suez Canal, and Gummy Bears

Remember the Suez canal debacle from 2021? That plus covid led to a lack of demand and then a shortage in semiconductors. Most of the parts of a car that are in any way advanced are controlled by microprocessors – even the key that unlocks your car has a teeny tiny computer in it.

So when car manufacturers began ramping down production due to a lack of semiconductors, something else was reduced too: the slaughtering of cows for leather. If you’re not making any new fancy cars with luxurious leather interiors, you don’t need to buy the leather, which means those cows don’t need to meet the business end of a cleaver.

Now, a byproduct of the slaughtering of cows is gelatine. It’s too expensive to kill cows just to harvest it, so manufacturers of Gummy Bears and other sweets buy this waste byproduct from the companies that slaughter cows for meat and leather.

And thus, because fewer people were buying cars and a 224,000-tonne vessel got wedged in a canal, fewer cows were being slaughtered, which made Gummy Bears too expensive to manufacture.

So, the output of your creative or knowledge work might not just be the thing itself – the song or the painting or the recipe – but the stuff you’ve learned in the process. Maybe you were fiddling with the reverb setting on your guitar amp and you discovered a sound that didn’t fit this particular song, but would probably work in another one… or you mistook salt for sugar when making your morning latte and you inadvertently invented salted caramel, in which case you deserve a knighthood.

It’s all feedback

Back in episode 5 we discussed the seesaw between boredom and anxiety, and that our brain is constantly seeking a state of homeostasis, or equilibrium.

Systems operate in much the same way, with positive and negative feedback pulling and pushing us on and off track. Positive feedback helps a system grow – you do a great gig, more people check you out on Spotify, your numbers go up, you release more music, people follow you online and bring their mates to your next live gig.

And while negative feedbac can compound just like positive feedback can, one type can turn into another. For example, your boss might get short-term rewards by screaming at her employees. This has a positive effect on output, but not for very long. After a while, the team becomes more and more resentful and they get burned out, which of course knocks the whole thing off course.

So if we think of our machine more as a cycle, we can see how input goes in, work happens, we get an output, and then from that output, we get feedback. That feedback then goes back into the machine, and the cycle begins again.

This is one reason it’s so important that you get your creative work out into the world. If you write beautiful poetry but you never perform it and you’re too afraid of judgement to let anyone read it, you’ll never get the feedback that might add some fuel to your next attempt.

If I make a dodgy meal and my guest doesn’t like it, I might be momentarily hurt, but it’s not like I’m never going to cook for them again. I’ll either make accommodations for that person in the future, or if their critique has merit, I’ll adjust my ratios the next time I cook something similar. It’s all just feedback.

So this notion I’ve been talking about since episode 7 about “how we’re all just people, man” isn’t just my hippy showing. And like Matthew and I talked about in last week’s episode, the systems we come up with for doing our best work have to work for other people too, not just ourselves.

And I know it might feel a bit cold and utilitarian to see each of us as just a machine, but remember everything, from the atoms that make up the platelets in our blood, to the planets that wind their way around the sun, are each part of a system. Systems are organic, they’re natural, they’re how a plant can turn photos of light into chemical energy. Each one needs careful maintenance, but with the right conditions, can result in pretty amazing things.